Essay writing 101 - what I learned in six years of writing essays

This guide is focused primarily on American Studies students and follows principles from the AS Writing Guide and MLA 9th edition.

Writing essays; some love it, some would banish it forever if they could. I have been taking classes that require me to write essays for the past six years, and I have arrived somewhere in the middle. I love working on my own research projects, but my motivation level often hits zero as soon as I actually have to start writing. With every essay project comes the challenge not to procrastinate the writing process. This article is not about that, though.

In the past few years, I have been doing a lot of essay-checking and peer-reviewing of the work of other students, next to my own writing projects. It allowed me to identify parts of essay writing that students find challenging. Whether it is structure, topic sentences, or maintaining a clear overview of all of your sources: there are things you can do to make your life easier. I may not have figured out how time management works, but I am able to share some tips that will help you make your essays stronger and your exam periods less overwhelming. We do not gatekeep at the American Studies Herald.

Tip 1: Topic sentences & a clear structure are best friends

One of the things American Studies professors try to push into your brain is that although writing good topic sentences may be hard, they are very important for your essay. And that’s true, but for many people creating good topic sentences remains confusing. How do you open a paragraph in an interesting way while also making the first sentence of every paragraph explain the paragraph’s topic?

My first tip would be to let go of the idea that the topic sentence has to be exciting. It is not the same as the opening line of your essay, which has to draw people in. A topic sentence is essentially just a small summary of the argument you are making in that particular paragraph. Knowing this, we can conclude two things:

- You should write your topic sentence after writing the rest of your paragraph. Yes, it is the opening statement of your paragraph, but you only know what you need to communicate in your topic sentence once the rest of your paragraph exists. Just write what you want in your paragraph without worrying about your topic sentence. After you finish your paragraph and are content with it, go back, and add a one-sentence summary of your argument in that paragraph. That is your topic sentence. This small summary does not include any explanations and details that are not part of your core argument. Let me illustrate this.

Imagine that you really want a certain type of car and have to write an essay about it. Your structure might look something like this:

Thesis: It would be a great idea for me to get a blue Fiat Panda because of its low fuel consumption and low costs, its hard-wearing interior, and its beautiful color.

Paragraph: would talk about the fact that the Fiat Panda you want to buy uses only a low amount of fuel per kilometer, which supports the thesis that it is a good idea to get this car. You would tell your readers about some fuel-related statistics and how much money it would cost you per month. After you have written the paragraph, you want to create the topic sentence. Your topic sentence has to convey the notion that it is a good idea to buy this car because of its low energy consumption, which consequently will lead to low costs for you, not the exact details about how much it will cost you exactly and how far the car will drive!

A bad example of a topic sentence: The Fiat Panda only uses 1 liter of fuel for 17 kilometers, meaning that it will only cost me 3,50 euros to get to work.

→ This is a poor topic sentence because you use examples that are part of your paragraph. They are evidence that support your reason to get a Fiat Panda, not THE reason, which is low consumption and low costs in general.

A good example of a topic sentence: The Fiat Panda is known for its low fuel consumption, which consequently leads to a financial burden that is lower than average.

→ After stating this topic sentence, it is time to bring out your evidence for this statement, which is the 1:17 consumption, for example.

Are you still following me? In short, your topic sentence is a short, concrete summary of the argument of your paragraph that does not include unnecessary details. Details are for your explanation. Of course, if you (for example) are analyzing a source in one of your paragraphs, you should name details such as the source’s name. If you are writing an analytical essay on anti-racism in the novel To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee, a topic sentence might look something like this:

“The way Atticus Finch treats his client during the trial in To Kill A Mockingbird (1960) shows an unprejudiced attitude that contrasts sharply with the other characters in the novel”

→ This topic sentence names essential details: name, the title of the book, character trait, and what you are trying to argue: that the novel shows non-discrimination through one of its characters. You do not tell the audience all the reasons why you are arguing this: you present your evidence after the topic sentence. That is why it is so important to write out your paragraph (your evidence) first and your topic sentence last.

- Secondly, your topic sentences are your best friends in keeping your essay structured and concise. You could view a successful essay as a solved math problem. Now don’t click away. I know we are all students at the Faculty of Arts, so I will try to keep this simple.

Topic sentence 1 + Topic sentence 2 + Topic sentence 3 + Topic sentence 4 (etc) = your thesis.

The goal is to write a convincing, well-structured essay that does not miss any essential details. A good way to check whether your structure, arguments and the order of your paragraphs are clear and logical, is to create a separate document and copy + paste your thesis statement and all of your topic sentences in a list beneath one another. If you read all your topic sentences together, you should have read the same message that your thesis statement is communicating. That is how you know that your topic sentences are clear. Your thesis statement, what you are trying to argue in your essay, is spread out over the number of paragraphs, which all support a small part. The topic sentences are small puzzle pieces that show you if the puzzle is complete.

Also, for the sake of your well-being: please create a writing plan beforehand. It will help you keep your head above the water during your writing process. In the essay plan, you should include all the evidence and quotes you will use to support your thesis statement. My essay plans look something like this (keep in mind that the structure changes according to the topic and approach of the particular essay):

| Introduction (aimed number of words) |

|

| Paragraph 1 – Background context and important terms (+ aimed number of words) |

|

| Paragraph 2: First argument (+ aimed number of words) |

|

| Paragraph 3: Second argument (+ aimed number of words) |

|

| Paragraph 4: Third argument (+ aimed number of words) |

|

| Paragraph 5: Fourth argument (+ aimed number of words) |

|

| Conclusion (+ aimed number of words) |

|

Writing a good thesis statement

The tips I wrote above should also help you write strong thesis statements. Your thesis statement is your core argument, so it should be concise and only contain essential arguments and details. I start writing my essay with a preliminary thesis in mind, and I always go back later to improve my thesis in the final version. This is because during the writing process, you might discover new things you would like to add to or remove from your argument.

Essentially, the most basic thesis statement format and accompanying essay structure look something like this:

Thesis: [My topic] shows [something] through/because of A, B, and C.

Sometimes there is a paragraph explaining background info or important terms here before your arguments*

Paragraph 1: [My topic] shows [something] through/because of A

Paragraph 2: [My topic] shows [something] through/because of B

Paragraph 3: [My topic] shows [something] through/because of C

(You are of course allowed to write more paragraphs to include points D, E, F, etc)

Conclusion: A, B, and C show [something] about [my topic] + a closing idea or question this conclusion makes you think of.

When you are (re)writing your thesis statement, include the most important keywords from your paragraphs. Name A, B, and C, but not why A, B, and C are true. That is what you describe in the separate paragraphs.

This is, of course, a little abstract, so I will place a thesis statement I wrote for one of my AS essays below. I’m not saying it is the most perfect thesis statement to ever exist, but I want to use it to point out some important details:

“In his 1987 speech in Berlin, Ronald Reagan communicates how the West had found in liberalism the optimal ideology to bring prosperity and peace. Furthermore, Reagan emphasizes that the ideological power of the people of Berlin had protected them from Soviet influences” (Global USA mini-essay).

→ The thesis statement talks about what Reagan communicates, not how he does it. My argument is about the message of Reagan’s speech, not his stylistic devices. My evidence exists of examples of how Reagan communicated the optimal features of liberalism, which can be found within my essay’s paragraphs.

→ It is unnecessary to start your thesis statement with “In this essay, I argue…”. You don’t need to do that to make your intentions clear. You can write your thesis statement with some confidence as if it were the truth, because if you have done enough research, you will be able to argue in your essay that your thesis is true. However, keep in mind that it is not wrong to start your thesis statement this way. All writers and professors have different preferences concerning this topic.

→ Your thesis statement can definitely consist of two sentences. It is more important that your audience can understand what you are going to argue than to keep your thesis as short as possible. Use commas, but don’t send your instructor into a coma because of sentences that are three pages long.

How to check if your argument is strong

Because every essay is different in topic and approach, there is not one way to tell you how to make a strong argument. However, there are some questions you can ask yourself to make sure your argument is as strong as possible:

- Is my argument new/surprising/interesting? You should always try to add something to other scholars’ ideas. What I mean by that is that you should just not repeat what others are saying, but what you can do is:

- Combine several ideas of other scholars to form a new argument. The particular combination of sources with your newly added point makes it unique. Always cite your sources!

- Analyze a primary source. Point out details of a movie, book, text, etcetera. This is an “easy” way to argue something new because it is your own interpretation. Be sure to always support your analysis with secondary sources.

- Is my structure logical? Do my topic sentences form a convincing argument if you take them together, and are the paragraphs in the right order?

- Do my conclusions correctly follow the information I found? Am I skipping steps in my arguments? Are there any other possible explanations I have not considered? Expect your reader to be critical, be one step ahead of them. Always question if there’s anything in your argument that could make the reader say, “yeah, but what about…”

- Am I arguing a topic that fits the scope of my essay? Your essay should bring something new to the table, but you don’t have to solve world problems in 2000 words. If your essay argues a wide array of things, it will come across as extremely chaotic. For a general A.S. essay, it is enough to stick to arguing one or two things in your thesis and use evidence to support that claim. Don’t be over-ambitious.

- Have I explained all important terms and things to my reader? Remember that you are not writing your essay to your professor, but rather to an academic audience that is interested in your essay but might not be an expert in your field. Also, it is good to realize that your audience is not in your head; they are not part of the thought-process that led you to your final conclusion. This means you will have to spell out your thoughts for your audience. What do certain key terms mean? What is the context of your primary source? Why are you making the argument you’re making? Why does it matter?

Citing your sources is a pain, but plagiarizing hurts even more

Using MLA 9 to cite your sources is tough to learn: there are so many details that go into it that it might seem hard to get it right. However, you will get called out for improperly citing your sources, so it is crucial to keep trying. Here are some things I learned over the years:

- Use Smartcat to cite your sources for you. If your source is available via the RUG library (AKA smartcat), there is a button called “export” in the top right corner of the source page that will generate the correct MLA bibliographic citation for you. Next to it is a button called “share”, which generates a short URL that you can add to the bibliography citation (as it often is generated with the text “MISSING URL”).

- Use Scribbr to generate your Works Cited list for sources you cannot find on Smartcat. The site offers multiple options for source types that you may want to cite, like journal articles or videos. What’s great is that it also gives you the correct in-text citation, which is the parenthetical citation you place in your essay whenever you use a source.

- ASH editor Mente recommends using Zotero to keep track of your sources, which is a free app and Chrome extension that will help you to create a works cited or bibliography with the click of one button. It will also help you with in-text referencing, and it has both a Google Docs and a Word extension!

- Do. Not. Use. Artificial. Intelligence. To. Write. Your. Essays.

Artificial intelligence chats can provide inspiration for your topic, but do not use them for actual information you will use in your essay. You will have to support all your evidence with sources, and AI sometimes makes up sources that do not really exist or contain wrong information. Be careful! - Fix your works-cited (the long citations at the end of your essay), before you start writing your essay, especially when you are short on time. Citing your sources can take surprisingly long sometimes, so please avoid the stress of citing everything in the last few minutes. I’m guilty of that and it brings your heart rate through the roof.

Speaking of in-text citations, this is something that many students struggle with as well. It is easy to get confused about where you place the period, for example. This is the right way to do it in MLA format:

“Quote” (Source [Page number]).

→ Try to remember it this way: “(). = High – round – low.

→ You always end the quote first with the second quotation mark, then you write your source within the parentheses, and only THEN do you put the period.

→ Notice how there is no comma between the source and the page number within the parentheses?

So what should you write down to identify your source within your in-text citation?

→ Most of the time, you can just put the author(s) last name(s). This is when your works cited citation looks like this:

Okpych, Nathanael J. Climbing a Broken Ladder: Contributors of College Success for Youth in Foster Care. Rutgers University Press, 2021. Smartcat, https://rug.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1227064905. Accessed 2023.

Your in-text citation would be (Okpych 23) if you quoted page 23.

→ Sometimes, there is no clear author, or you use several works of the same author in your essay. In that case your in-text citation would contain (a part of) the title of the source. This would look like (”climbing a broken ladder” 23). If you cite several sources by the same author, it can get confusing what source you are talking about if you only cite the author’s last name, so that is why you use the title instead. If the title is long, you can shorten it (”Climbing” 23).

→ In the case that your source is written by three or more authors, you write the first author with “et al.”, which means “and others”. Your In-text citation will look like this: (Ortega et al. 23)

→ Of course, there are always other types of sources that require different types of citations, but these are the main forms. If you are unsure how to cite your source type correctly, google “how to cite [your source-type] in MLA 9”, and you will find websites like owl.purdue.edu and libguides.com that will help you.

Staying organized in a sea of sources

Dealing with many different sources can be quite overwhelming: you don’t want to lose them, you want to know which ones you read and what you still have to do, etc. I want to introduce you to an organizational tool that will make your academic life easier: Notion

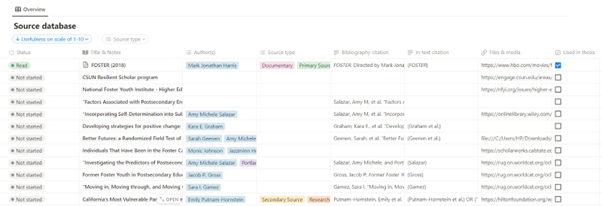

Notion is a website and app for Mac, Windows, IOS and Android that allows you to save all your notes in one place: it is essentially one large personal database. I use it for many things, but it has turned out to be especially helpful in organizing the source base for my BA Thesis. This is because Notion allows you to create database-tables in which you can save all of your sources, accompanying notes and things such as keywords and citations. What is also great about the tool is that it allows you to filter for certain features. I can ask Notion to filter for all sources that are marked as secondary sources and books, and it will only show those sources. Best of all: Notion is completely free! Of course, you could also create something similar in Word or Google Docs with the table function, but it won’t allow you to store your notes within the table itself.

To give you an idea what that could look like, this is a screenshot of my thesis database:

I know this might look a little difficult and intimidating, so I created a free Notion template you can use and edit after you have created a free Notion account. You can find it via this link: Free template made by me. If you click “duplicate” in the top right corner, you will be able to use the page in your own Notion system.

The possibilities with Notion are endless, and you can find many videos on youtube that explain all the ways you can use it to optimize your productivity! If you sign up with your RUG email, you even get access to the premium version for free.

I hope this essay 101 helped you out a little. Remember that, above all other things, writing essays is something you learn through practice. Don’t give up if you don’t succeed at the first few attempts, and help one another by reading through each other’s work! We’re all in this together.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

End of Article